MA ECONOMICS EXTERNAL 2010 EXAMS KU..GUESS PAPERS ARE AVAILABLE

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies how individuals, households and firms and some states make decisions to allocate limited resources, typically in markets where goods or services are being bought and sold. Microeconomics examines how these decisions and behaviors affect the supply and demand for goods and services, which determines prices; and how prices, in turn, determine the supply and demand of goods and services. Following is the working of this branch in the economy In a nutshell, microeconomics has to do withSUPPLY andDEMAND, and with the way they interact in various markets. Labor economics, for example, is built largely on the analysis of the supply and demand for labor of different types. The field of industrial organization deals with the different mechanisms (MONOPOLY,CARTELS, and different types of competitive behavior) by which goods and services are sold. International economics worries about the demand and supply of individual traded commodities, as well as of a country’s exports and imports taken as a whole and the consequent demand for and supply of FOREIGN EXCHANGE. Agricultural economics deals with the demand and supply of agricultural products and of farmland, farm labor, and the other factors of production involved in agriculture. Public finance (see PUBLIC CHOICE) looks at how the government enters the scene. Traditionally, its focus was on taxes, which automatically introduce “wedges” (differences between the price the buyer pays and the price the seller receives) and cause inefficiency. More recently, public finance has reached into the expenditure side as well, attempting to analyze (and sometimes actually to measure) the costs and benefits of various government outlays and programs. Applied welfare economics is the fruition of microeconomics. It deals with the costs and benefits of just about anything—government projects, taxes on commodities, taxes on factors of production (corporation income taxes, payroll taxes), agricultural programs (like price supports and acreage controls), tariffs on imports, foreign exchange controls, various forms of industrial organization (like monopoly and oligopoly), and various aspects of labor market behavior (like MINIMUM WAGES, the monopoly power of LABOR UNIONS, and so on). At the root of everything is supply and demand. It is not at all farfetched to think of these as basically human characteristics. If human beings are not going to be totally self-sufficient, they will end up producing certain things that they trade in order to fulfill their demands for other things. The specialization of production and the institutions of trade, commerce, and markets long antedated the science of economics. Indeed, one can fairly say that from the very outset the science of economics entailed the study of the market forms that arose quite naturally (and without any help from economists) out of human behavior. People specialize in what they think they can do best—or more existentially, in what heredity, environment, fate, and their own volition have brought them to do. They trade their services and/or the products of their specialization for those produced by others. Markets evolve to organize this sort of trading, and money evolves to act as a generalized unit of account and to make barter unnecessary. In this market process, people try to get the most from what they have to sell, and to satisfy their desires as much as possible. In microeconomics this is translated into the notion of people maximizing their personal “utility,” or welfare. This process helps them to decide what they will supply and what they will demand. Nine times out of ten, the excess demand will end up being reflected in a gray or black market, whose existence is probably the clearest evidence that the official price is artificially low. In turn, economists are nearly always right when they predict that pushing prices down via price controls will end up reducing the amount supplied and generating black-market prices not only well above the official price, but also above the market price that would prevail in the absence of controls represents the artificial restriction of production by an entity having sufficient “market power” to do so. The economics of monopoly are most easily seen by thinking of a “monopoly markup” as a privately imposed, privately collected tax. This was, in fact, a reality a few centuries ago when feudal rulers sometimes endowed their favorites with monopoly rights over certain products. The recipients need not ever “produce” such products themselves. They could contract with other firms to produce the good at low prices and then charge consumers what the traffic would bear (so as to maximize monopoly profit). The difference between these two prices is the “monopoly markup,” which functions like a tax. In this example it is clear that the true beneficiary of monopoly power is the one who exercises it; both producers and consumers end up losing.

Modern monopolies are a bit less transparent, for two reasons. First, even though governments still grant monopolies, they usually grant them to the producers. Second, some monopolies just happen without government creating them, although these are usually short-lived. Either way, the proceeds of the monopoly markup (or tax) are commingled with the return to capital of the monopoly firms. Similarly, labor monopoly is usually exercised by unions, which are able to charge a monopoly markup (or tax), which then becomes commingled with the wages of their members. The true effect of labor monopoly on the competitive wage is seen by looking at the nonunion segment of the economy. Here, wages end up lower because the union wage causes fewer workers to be hired in the unionized firms, leaving a larger labor supply (and a consequent lower wage) in the nonunion segment. Artificially high urban wages attract migrants from rural areas. If the wage does not adjust downward to equate supply and demand, the rate of urbanUNEMPLOYMENT will rise until further migration is deterred. Still other examples are in banking and drugs. When the “margin” in banking is set too high, new banks enter and/or branches of old ones proliferate until further entry is deterred. Artificially maintained drug prices led, in several Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay before their major liberalizations of recent decades), to a pharmacy on almost every block. The great unifying principles of microeconomics are, ever and always, supply and demand. The normative overtone of microeconomics comes from the fact that competitive supply price represents value as seen by suppliers, and competitive demand price represents value as seen by demanders. The motivating force is that of human Beings, always gravitating toward choices and arrangements that reflect their tastes. The miracle of it all is that on the basis of such simple and straightforward underpinnings, a rich tapestry of analysis, insights, and understanding can be woven. This brief article can only give its readers a glimpse—hopefully a tempting one—of the richness, beauty, and promise of that tapestry.

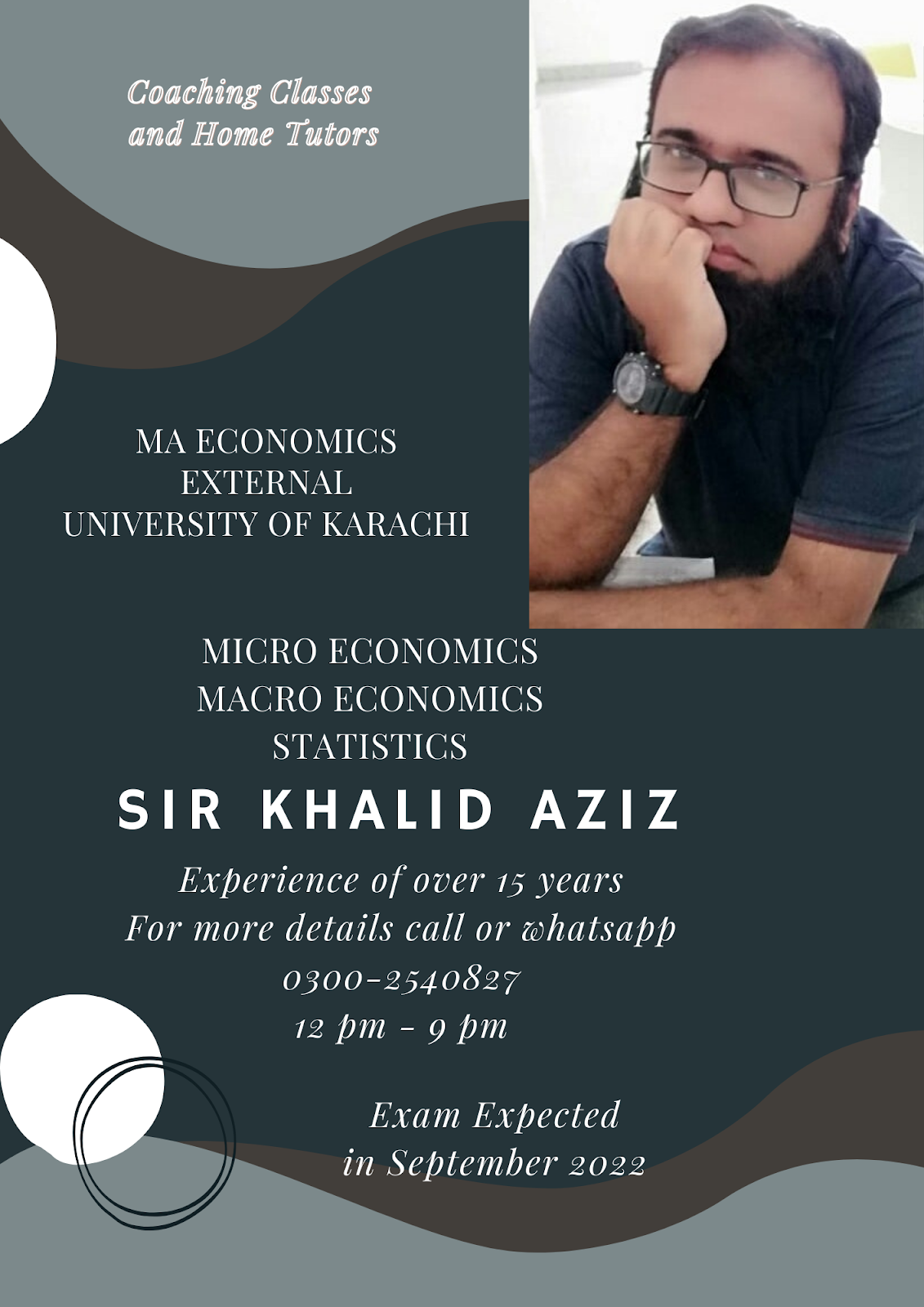

MA ECONOMICS

NOTES AVAILABLE IN REASONABLE PRICE

Macroeconomics and Microeconomics: Chit Chat

CHIT-CHAT TIME Commerce Heaven (In this conversation after getting 1000 Rupees Khalid is going with his friend Tariq to purcha...

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

-

CHIT-CHAT TIME Commerce Heaven (In this conversation after getting 1000 Rupees Khalid is going with his friend Tariq to purcha...

-

Definition and Explanation: Classic economics covers a century and a half of economic teaching. Adam Smith wrote a classic book entitled, ...

-

Offer Curve Diagram Tariff A B A&B Expansion A B A&B Variants: Inelastic Demand by ... Country A...

Total Pageviews

CLASSES

Guess Papers

No comments:

Post a Comment